Starting a low oxalate diet? Going low oxalate can be a huge step into a brand-new world. It’s not only unfamiliar but somewhat disorienting. What to eat? How much to eat? What should your new staples be? How will you learn and remember which foods are high in oxalate? You need practical guidance—and a bit of data on how much oxalate is in your foods.

When you’re researching the oxalate content of foods, where do you turn first? Probably Google. But most internet sites offer scant information laced with factual errors. As you comb through the search results for that list of oxalate-rich foods, you could easily find different websites that don’t agree with one another. A given food may be listed as high on one site and low on another. The lists are also often short, with just a few foods listed. The “top ten” is far from the whole story!

Obviously, the easy-to-find data isn’t especially good. And this mess can be a big, discouraging curve-ball. Don’t let all this conflicting information and lack of consensus among various data resources get you down! It is still possible to succeed in adopting a healthier, oxalate-aware way of eating.

Still, making sense of the data can overwhelming and confusing. It was for me, despite my nutrition education and professional experience. To get you oriented and make you more fool-proof, let me walk you through the mine-field of oxalate content confusion.

Online Lists Will Keep You Feeling Confused About Oxalates in Foods

How can you tell which information is credible? You won’t know just by looking at the list. Fame and fortune (institutional reputation such as USDA, Harvard, or WebMD, for example) do not assure you that a list is correct.

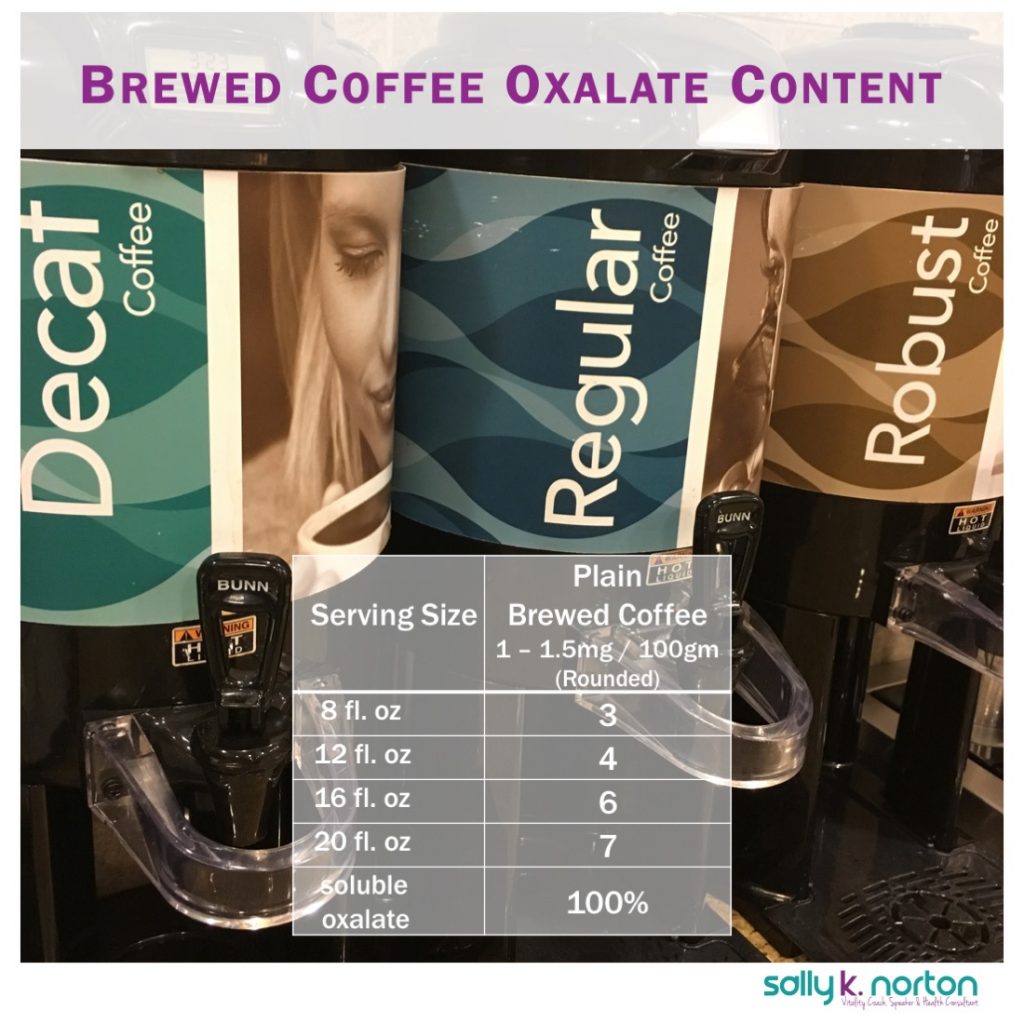

Misinformation about oxalates is widespread, especially among mainstream sources! For example, there’s one false claim that dates are high in oxalate posted on WebMD and thus elsewhere. (Please see my short post on the error with dates here, coming next week). There is also confusion about oxalate content in coffee because some researchers claim coffee is a high oxalate food. Neither is true. Multiple credible sources prove that in both cases, the sites listing dates and coffee as high oxalate are wrong. But mistaken notions persist. And mistaken data goes uncorrected.

Most list makers fail to mention where they got their information, let alone who did the testing and by which methods. Nor do the list makers bother to explain their rationale for designating foods as “high” or “low” in oxalate. And they rarely (if ever) revisit old information and update it.

Since the online lists aren’t good enough, surely medical journals, health agencies, and academia must have trustworthy numbers, right? But if you put on your thinking cap and take a deep dive into the literature, you might have a hard time finding much. In the end, what you manage to dig up from professional papers is also conflicted and confusing. It’s frustrating and frankly shocking how difficult it is to find credible, consistent resources on oxalates in our foods.

The full value of low-oxalate eating is not yet well-known, and sufficient resources have not been assigned to the necessary work.

Despite the jumble of imperfect science, incomplete data, and untrustworthy conclusions about what amount is safe to consume, we can still find our way to low oxalate eating and heal from oxalate toxicity.

How to Get Better Information

Despite the data muddle, you can transition to this eating strategy successfully. Start with my Beginners’ Guide. This vetted, trustworthy list will get you 90% of the way there.

Read on if you want to understand more about the state of oxalate data and why it can be challenging. Remember that enduring some confusion is part of learning.

In the remainder of this post, I’ll attempt to explain the reasons for the discrepancies in oxalate data.

Better Sources Exist for Oxalates in Foods

I want to reassure you that there is enough credible information to support low-oxalate eating. Today we have more knowledge than ever before on oxalate in foods and how they impact health. The work of The VP Foundation and Susan Owens’ Trying Low Oxalates Facebook group has helped to launch our emerging era of growing awareness of oxalate overload. As more of us discover the healing benefits, our growing oxalate-aware community can continue to improve the data, making it more accessible, understandable, and usable over time. Most importantly, we all need to advocate for more food testing.

For a better understanding of the oxalate content of foods and using oxalate data, keep the following five tips in mind.

Need to Know Tip #1: Oxalate Levels Vary for the Same Kind of Food.

Plants naturally produce oxalates for survival to ward off microorganisms, fungi, and plant eaters. It also helps them to discard excess calcium they pick up from soils.

Oxalate levels can also vary between different types of the same food. Let’s look at apples as an example, which have over 7,500 varieties grown worldwide. I know of only 24 tests of apples. An Egyptian study found an apple of average size (~ 6 oz) had 15 mg of oxalate, but it doesn’t indicate which type of apple. Meanwhile, other tests conducted in the US found that a Pink Lady apple contains 2 mg of oxalate, a Gala has 2 to 5 mg, and a medium Granny Smith contains 5 mg. Based on a set of tests done for the VP Foundation, variations in oxalate content between varieties of tomatoes is far wider.

Situational factors such as soil content, pH, and weather can impact how much oxalate each plant contains. Unless you test every individual fruit, vegetable, or slice of bread you eat, it’s impossible to know exactly how much oxalate it has. Research reports typically don’t indicate variety, maturity, and other factors with their test results.

Current research typically does not seriously investigate variability in foods. And we don’t know how much each type varies and what factors influence this variability. Different growing conditions may explain the difference between US-grown apples and those grown in Egypt. Thankfully, the amounts in apples are relatively low.

Many foods, herbs, and supplements have only been tested (and reported) once. This means we are unsure of the estimated content for these rarely tested items. Because of natural variation and limited testing, I suggest that you think about the numbers around oxalate levels as somewhat “fuzzy.”

Need to Know Tip #2: Oxalate in Foods Information is Incomplete

What really brings us garbage data are the human factors. It might be the testing method used, sloppy execution of the testing, or inaccurate reporting that explain the 5-times higher oxalate content of the Egyptian apple, and not the apples’ natural variability after all. Without more resources and interest by researchers, we don’t know.

We need to retest many foods to understand the extent of this variability, reveal mistakes, and reduce confusion around the oxalate content of what we eat.

Additionally, plants produce two types of oxalates. The first, oxalic acid, is soluble and is easily absorbed into your bloodstream. The second, oxalate crystals, are insoluble, irritate your digestive tract, but probably don’t enter the bloodstream. Both types of oxalate can impact your body, but in different ways. Many reports don’t make this critical distinction. Only recently has it become common for researchers to distinguish between the two categories of oxalate in their reporting. This can add to the confusion.

Need to Know Tip #3: Sloppiness is Widespread

Some researchers use unreliable methods in their analysis. (See my coffee post on this problem.) In another case, testing done for the VP Foundation mistakenly used too small a sample in testing oils and got numbers overstating their oxalate content, which is in reality essentially zero. Later, they repeated the testing and reported corrected data. But in both cases the old, wrong data continues to circulate.

Many reports also fail to mention food preparation—such as whether something was tested raw, steamed, boiled, or fried—which can significantly impact oxalate levels and the data’s usefulness for estimating how much oxalate you are eating. All of these factors can create bad data.

There may also be simple data entry mistakes (aka, “typos”) causing confusion. Even our most reliable source of oxalate data, the VP Foundation, has reported several items incorrectly. For example, when they calculated the oxalate in one ounce (28 grams) of sweet potato chips, they mistakenly used “17 grams” instead of 28 grams because one ounce is about 17 chips. Thus, they mis-reported the amount of oxalate per one ounce serving as (37 mg oxalate), which is much lower than it really is (60 mg).

Tamarillo and Tamarind are not the same thing

Here’s another example of a reporting error: the experienced German researchers, Hönow and Hesse, said they tested “tamarillo” (a Central and South American tree fruit in the nightshade family) but they described it as “tamarindus indica” (the Indian fruit taramind). Those are entirely different foods, and we don’t know which one they tested. Thus, it’s garbage data, and probably worse than useless.

I’m not bashing anyone with these examples. What you need to realize is this: These mistakes are very easy to make. Even the best data sources contain them. You need to use your head when looking over the data.

Data discrepancies and misunderstandings about oxalates in foods could have critical implications for our health. The scientific community needs to step up to ensure they are not the reason for the confusion. Unfortunately, taking the time to get the facts right is an unusual approach!

Need to Know Tip #4: Older Oxalate Testing Methods Were Less Accurate

Prior to 1980 or so, the usual testing was prone to error. One important source of error affected tests of foods that have very little oxalate but contain abundant vitamin C. For example, the USDA data (published in dietitians’ handbooks) states that radishes are high in oxalate. But they are, in fact, very low. If the vitamin C in the radishes degraded to oxalate during testing it might be a partial explanation for the error. Or, perhaps it’s just bad data management, yet again.

Accurate testing continues to be challenging, but more recent testing tends to offer more reliable information.

Need to Know Tip #5: Oxalate Data Researchers do not Calculate Portion Sizes

To make things more complex for consumers, researchers often don’t translate their numbers into amounts per typical portion size in their reporting. They might, for example, present the results based on the dry weight without calculating the oxalate content of the food as it is normally consumed (including the moisture that was removed before analysis).

Let’s go back to the coffee example. One test of instant coffee found 57 mg oxalate per 100 grams of coffee powder. That sounds like a lot! As I explained in my blog post about coffee, you only use one-half to one gram of instant coffee to brew a cup.

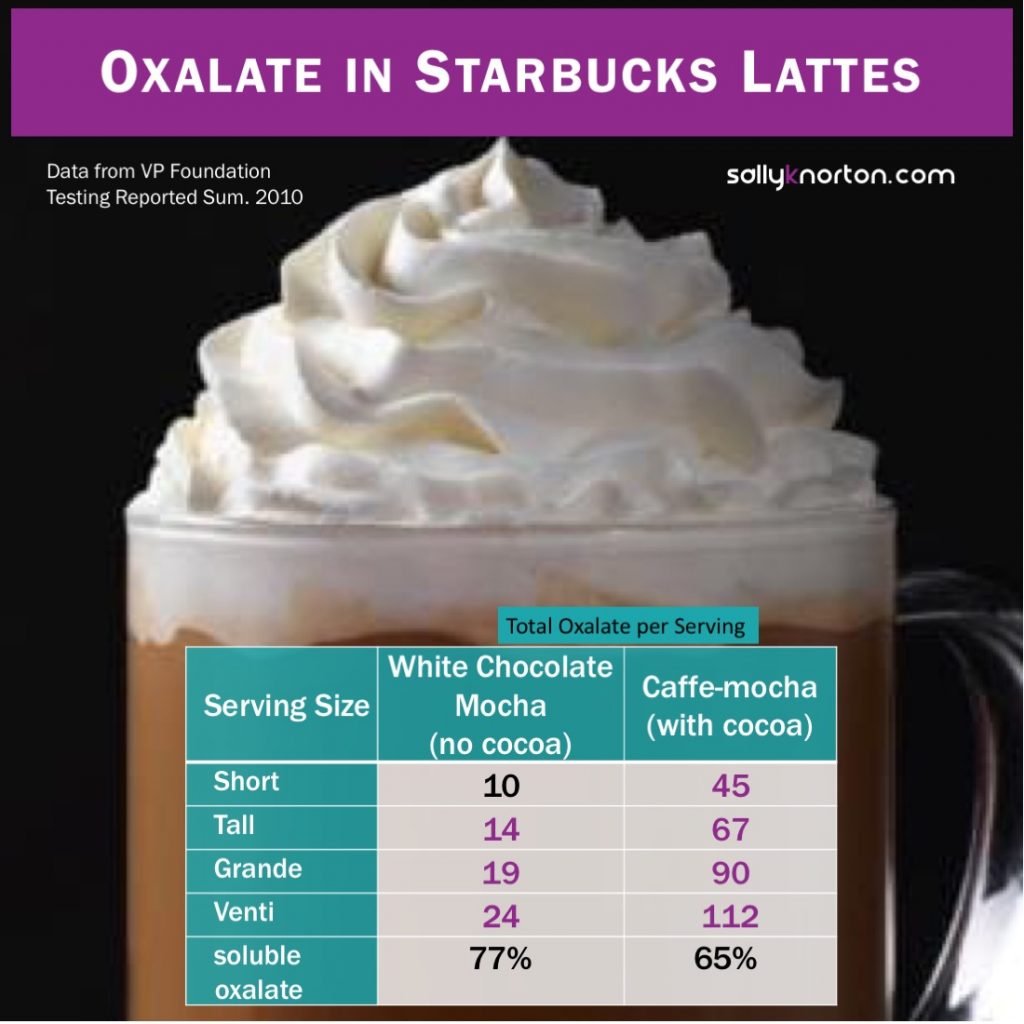

Unless you’re choking down an entire cup of undiluted instant coffee powder—or adding high oxalate ingredients like cocoa to make a mocha—coffee is a low-oxalate food. Even if you drink a Venti dark roast from Starbucks every morning (which I don’t recommend because of the caffeine and other chemicals in coffee), you’re not drinking very much oxalate. In addition to how it’s prepared, portion sizes will impact how much oxalate you consume. Researchers need to do a better job at taking portion sizes into account when publishing reports so that consumers can use the data correctly.

We Need More (and Better) Research on Oxalates in Foods

There are significant knowledge gaps in the current literature regarding oxalates in foods and oxalate toxicity. More research is required to understand how much oxalate various foods contain, how much it varies from one variety to another (or for other reasons such as ripeness), and to weed out the technical errors and mistaken conclusions that linger in obsolete publications and in the minds of researchers, doctors, and the unsuspecting public. Unfortunately, “weeding” of medical literature is not something journals have any incentive to bother with, and it is difficult to execute.

It’s enough to make anyone’s head spin, but I have good news: going low oxalate isn’t about bean-counting. It isn’t about strictly accounting for everything you eat or measuring the exact amount of oxalate down to the milligram.

This isn’t Weight Watchers. I dislike tracking everything I eat. It can be distracting, demanding, and impractical. You can successfully lower your oxalate intake without sweating the data details. However, if you love to track things, please do. It will help if you know what you actually ate instead of just what you remember eating.

Practice Tip #1: You Don’t Have to be Perfect

Going low oxalate is about awareness and consistency, not perfection. We have enough information about oxalates in foods that we can make educated decisions about how to structure our diets without getting too hung up on what we’re eating.

Despite the limitations of oxalate data, we know that certain foods are reliably low in oxalate, including meat, poultry, dairy products, fats, true lettuces, white rice, several herbs (dill and thyme, for example) and spices (white pepper, mustard, cayenne pepper), as well as most vegetables in the cabbage family. If you build your diet around these staple foods, you will have no trouble keeping your oxalate levels in a safe range.

Practice Tip #2: Portion Size Matters

Portion size is critically important. Eating one bite of a high-oxalate food, like chocolate cake, is very different from eating an entire slice. Another example would be choosing ONE (normal-sized) chocolate chip cookie instead of a fudge brownie or mug of hot cocoa. While I don’t recommend throwing caution to the wind, you don’t need to sweat occasionally eating a tiny amount of high-oxalate foods (like a few chocolate chips).

Photo by Valiant Made on Unsplash

For example, spinach is a high-oxalate food I recommend avoiding. However, if you order a salad at a restaurant, realize some spinach leaves are mixed in, and you accidentally ate one or two of them, don’t worry: you won’t cause more oxalate to collect in your body. Just pick out the rest of the leaves and make sure the remainder of your meal is built around lower-oxalate foods. In fact, by eating small amounts of oxalate, you might avoid or delay heavy oxalate clearing symptoms. That is a good thing.

On the other hand, giving yourself permission to ignore what you’re eating can be a mistake. For example, taking several solid bites of an intense fudge brownie has the potential to bring on symptoms within one to five hours after the indiscretion. It’s not tragic if it happens, but it’s also easy to avoid if you pay attention.

Practice Tip #3: Keep Learning

Going low oxalate is a nuanced process, and there’s always more to learn. As you transition into low-oxalate eating, I’m here to help you make sense of the information that’s out there.

Get the “big rocks” right by using my Beginner’s Guide to trim out the worst offenders and adopt the “safe bets.” The middle ground foods? I’ll help you with that too, but don’t sweat them in the first phase of getting off the dangerously high foods. Tables available via my group meetings and in my book, Toxic Superfoods, will give you further guidance. For lots of specific data, my forthcoming Oxalate Data Resource Manual will provide you with all the particulars currently available for refining your oxalate-aware diet.