If you are taking 500 mg or more vitamin C daily, there is something you need to know. Vitamin C (in excess) can become a toxin that can lead to kidney stones, arthritis, other pain conditions, and perhaps, compromised brain function. For decades we have been told that vitamin C is good for us and may help prevent colds. But too much of a good thing can make trouble. (Research has not been able to confirm the theory that vitamin C supplements help to prevent colds unless you routinely engage in physically demanding work or endurance sports.) [Read more…]

Standing on Steady Ground: Resisting New Ideas

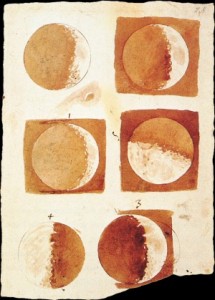

Most people will find certainty and safety by subscribing to widely held ideas, regardless of the “truth” of those ideas. Likewise, institutions and the people that are governed by them resist new explanations for phenomena. A classic example of this is found in the dawn of two radical ideas that 1) the earth moves around in space, and 2) the earth revolves around the sun. [Read more…]

Most people will find certainty and safety by subscribing to widely held ideas, regardless of the “truth” of those ideas. Likewise, institutions and the people that are governed by them resist new explanations for phenomena. A classic example of this is found in the dawn of two radical ideas that 1) the earth moves around in space, and 2) the earth revolves around the sun. [Read more…]

I missed a key footnote in college about oxalates in food

Sweet potatoes, walnuts, and kiwi are no longer my friends. Apparently, they never were. I just never got the memo.

My nutrition education hadn’t warned me that a variety of vegetables, nuts, and fruits could cause health problems due to their oxalate content. Instead, my college textbooks suggested that toxic oxalate is confined to a short list of five foods. My old Basic Food text states: “… oxalic acid, which occurs in spinach, chard, beet greens, and rhubarb, is toxic” (p.17)1. Another textbook, Normal and Therapeutic Nutrition, added coco to this same list, bringing the total up to five foods with oxalic acid (p. 134)2. Later in the therapeutic section of Normal and Therapeutic Nutrition, the authors added 15 more foods to the list in the one and only paragraph devoted to dietary restriction of oxalate (p. 675). The oxalate-restricted diet is described in under 60 words.

Truth be told, lab methods for measuring oxalate in foods did not become reliable until about 1980. Today in 2015, the nutrition profession still lacks complete or accurate reference for the oxalate content of foods and supplements. And, we have not fully described or tested the hypothetical oxalate-restricted diet, because we lack sufficient data and other tools needed to do so. Such a diet can only be created by an opt-in method of building a diet with foods that have been accurately tested for oxalate content. Given the ubiquitous nature of oxalate in foods, the old notion of avoiding the top 20 high-oxalate foods is illogical and mathematically unsound. Yet, this is exactly the standard of practice today. In the rare instance when the oxalate-restricted diet is prescribed, the patient is handed an inaccurate list of the highest oxalate containing foods and told to limit these foods to occasional, moderate portions.

The chief message contained in my college text books about oxalic acid in foods is this: Oxalic acid reduces the amount of calcium that can be absorbed from very high oxalate foods to nearly zero, although the food composition reference tables list spinach and other greens as containing calcium, in significant amounts. From a nutritional standpoint these foods lack calcium because it is bound to oxalic acid and cannot be used by the body. These two textbooks disagree about the resulting loss of calcium availability as a result of adding chocolate (oxalic acid) to milk. When I was in school designing menus to meet nutritional requirements laid out by the FDA, we were not graded down for including, and counting, un-available calcium (in known high oxalate foods) in our meal plans. Oxalate was considered a non-issue back then, and still is today. In fact, high-oxalate foods are widely and loudly promoted as healthy foods.

My college textbooks also reassured me that oxalic acid “does not cause illness in the amounts that are normally consumed”. In today’s world proclaiming the healthy virtues of veganism, raw foods, and vegetable juicing, this dismissive and untested assertion sounds irresponsible. There is a growing body of evidence that oxalates can accumulate in tissues, not just the kidneys, which can lead to a variety of connective tissue and other problems in susceptible individuals. My Basic Foods book promoted the idea of increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables without a thought to the possibility that people could get into trouble with excessive amounts of naturally occurring oxalate in their foods. It didn’t occur to them that I had (while in college) a garden patch of Swiss chard which I ate in large portions every day for 2 months. At the time I was using crutches and 3600mg of ibuprofen to curb the constant foot pain that persisted after having surgery on both of my feet three years earlier in 1986. Today, I am pretty sure about the reason my feet were not healing properly – the toxic oxalic acid in my vegetarian diet and already in my body was interfering with healing.

So the seed was never planted in my head while in college, that over-doing Swiss chard and other high-oxalate foods could be trouble. It turns out that it can bring one’s productive life to a halt, as it did mine – several times.

References

- June C. Gates. Basic Foods. (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1981).

- Corinne H. Robinson & Marilyn R. Lawler. Normal and Therapeutic Nutrition. (Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc., 1982).