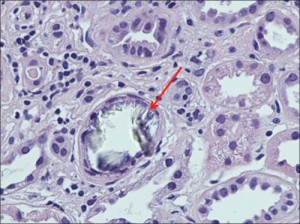

Figure 1 Nagaraju (2013). Large intraluminal translucent crystals of calcium oxalate, tubular epithelial degeneration (foamy cytoplasm, pyknosis, karyorrhexis, indistinct cell borders, dilated lumina), lymphocytic infiltration in the interstitium (H and E, ×400)

A case of kidney failure after bariatric surgery is stopped with low-oxalate diet.

Canadian nephrologists reported a case of life-threatening kidney damage caused by kidney deposits of oxalate crystals.1 The doctors performed a kidney biopsy on their patient, a 54-year old man, 20 months after duodenal switch weight-loss surgery. His blood creatinine levels had tripled over the previous nine months. The biopsy found oxalate crystals causing tubular damage and atrophy, fibrosis, and inflammation. They also noted hardening of the blood-filtering glomerular capillaries.

The patient was treated with a low-oxalate diet, calcium citrate (1,000 mg 3 times a day with meals), high water consumption, and the drug cholestyramine to help reduce oxalate absorption. This stabilized his blood creatinine levels and his urine oxalate dropped by a third from 99 to 63mg per day. Normal urine oxalate is under 40-45 mg/day. The authors’ want practicing clinicians to be aware of the increased risk of excessive absorption of oxalates from food following weight-loss surgery (“secondary enteric hyperoxaluria”) which can lead to kidney stones and life-threatening renal failure due to oxalate-induced kidney damage.

This case illustrates: 1) changes to gut function can alter oxalate absorption; 2) oxalates in foods can cause tissue damage; and 3) this process may be arrested by limiting oxalate absorption with a low-oxalate diet and supportive therapies.

Interestingly, this patient’s urine oxalate levels, although lower, remained elevated (63mg/day) despite effective diet therapy. Consistent with reports from cases of genetic oxalosis, this may indicate that the patient’s tissues are shedding existing oxalate deposits in the kidney and elsewhere in the body. The clearing of oxalate deposits may contribute to urinary oxalate, perhaps for years. It is likely that shrinking tissue oxalate deposits leave in their wake persistent renal scarring and tissue damage elsewhere.

Oxalate deposits can develop over time after either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) or duodenal switch surgery. These surgeries can trigger an increase in the absorption of dietary oxalates (perhaps due to bile salts in the colon and fat malabsorption in the small intestine). This potential complication -the possibility of increased oxalate absorption leading to high urine oxalates and, eventually, kidney failure – is not typically discussed at the time of consent to surgery.2 Nor are these patients typically told that they can minimize the risk by modifying their diet to avoid oxalates in foods. Discharge and follow-up counseling and education should include instructions for the low-oxalate diet. The gastric banding procedure is not likely to cause this problem.2

Oxalate deposits in the body develop gradually and often without symptoms.3 Although rarely prescribed by clinicians, a low oxalate diet can help avert the risk of too much oxalate and may be especially important for people with intestinal and digestive problems, including, but not limited to weight-loss surgery.4 Other surgical procedures (intestinal resection, ileostomy, bladder diversion surgery) and GI conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), pancreatic insufficiency, or poor fat digestion (steatorrhea) can also contribute to excessive absorption of oxalates in the digestive tract.

The renal damage caused by oxalates may not be reversible so it is important to start the low oxalate diet as early as possible. Anyone who is increasing their water intake or taking calcium citrate to reduce absorption of oxalates needs to be aware that timing is important. Water with meals can increase oxalate absorption, so drink fluids between meals. Also, calcium citrate tablets need time to dissolve, so take them about 20 minutes before meals to maximize the oxalate sequestration effects.

Key Point: Dietary oxalates can cause kidney failure after bariatric surgery. The progression of the disease can be halted by the low-oxalate diet, if implemented correctly and early enough.

For my low-oxalate grocery shopping list click here.

References

- Nagaraju SP, Gupta A, McCormick B. Oxalate nephropathy: An important cause of renal failure after bariatric surgery. Indian J Nephrol. 2013;23(4):316-318. doi:10.4103/0971-4065.114493.

- SenthilKumaran S, David SS, Menezes RG, Thirumalaikolundusubramanian P. Concern, counseling and consent for bariatric surgery. Indian J Nephrol. 2014;24(4):263-264. doi:10.4103/0971-4065.133045.

- Marengo S, Zeise B, Wilson C, MacLennan G, Romani AP. The trigger-maintenance model of persistent mild to moderate hyperoxaluria induces oxalate accumulation in non-renal tissues. Urolithiasis. 2013;41(6):455-466. doi:10.1007/s00240-013-0584-5.

- Lieske JC, Tremaine WJ, De Simone C, et al. Diet, but not oral probiotics, effectively reduces urinary oxalate excretion and calcium-oxalate supersaturation. Kidney Int. 2010;78(11):1178-1185. doi:10.1038/ki.2010.310.

Further Reading about Bariatric Surgery and Oxalates

- Agrawal V, Liu XJ, Campfield T, Romanelli J, Enrique Silva J, Braden GL. Calcium oxalate supersaturation increases early after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis Off J Am Soc Bariatr Surg. 2014;10(1):88-94. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2013.03.014.

- Ahmed MH, Byrne CD. Bariatric surgery and renal function: a precarious balance between benefit and harm. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(10):3142-3147. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq347.

- Asplin JR. Hyperoxaluria and Bariatric Surgery. In: AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol 900. AIP Publishing; 2007:82-87. doi:10.1063/1.2723563.

- Froeder L, Arasaki CH, Malheiros CA, Baxmann AC, Heilberg IP. Response to Dietary Oxalate after Bariatric Surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2012;7(12):2033-2040. doi:10.2215/CJN.02560312.

- Kumar R, Lieske JC, Collazo-Clavell ML, et al. Fat Malabsorption and Increased Intestinal Oxalate Absorption are Common after Rouxen-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. Surgery. 2011;149(5):654-661. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2010.11.015.

- Lieske JC, Mehta RA, Milliner DS, Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Sarr MG. Kidney stones are common after bariatric surgery. Kidney Int. October 2014. doi:10.1038/ki.2014.352.

- Nasr SH, D’Agati VD, Said SM, et al. Oxalate Nephropathy Complicating Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: An Underrecognized Cause of Irreversible Renal Failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2008;3(6):1676-1683. doi:10.2215/CJN.02940608.

- Patel BN, Passman CM, Fernandez A, et al. Prevalence of Hyperoxaluria After Bariatric Surgery. J Urol. 2009;181(1):161-166. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2008.09.028.

- Ritz E. Bariatric surgery and the kidney – Much benefit, but also potential harm. Clin Kidney J Clin Kidney J. 2013;6(4):368-372.

- Whitson JM, Stackhouse GB, Stoller ML. Hyperoxaluria after modern bariatric surgery: case series and literature review. Int Urol Nephrol. 2010;42(2):369-374. doi:10.1007/s11255-009-9602-5.

Very informative about this low oxalate eating to improve my health. I like this!

Approximately 150000 bariatric procedures are performed in the US annually. Neurologic complications arise in as many as 5% of individuals having this surgery. (Due to poor absorption of nutrients.)

Ref: The neurologic complications of bariatric surgery. Berger JR & Singhal D. (2014).

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24365339