One of the most common questions I get when people hear about the health dangers of oxalates is whether coffee is “low” or “high” in oxalate. It’s a good question. After all, most everyone I know depends heavily on coffee to function. This article is not about the wisdom of your caffeine addiction, however. It’s about knowing how much oxalate you’re (not) consuming. To this end, I compiled all the published analyses of the oxalate content of coffee I could find in an attempt to understand why this is a question at all.

It should not have surprised me that looking to scientific reports for answers unearthed a golden example of how bad science comes to pass for truth. We the public don’t know when terrible science is influencing our thinking or inflaming our fears about oxalate in coffee. And we are easy dupes. Our tweet-sized attention span and resistance to technical details makes us headline readers, not thinkers.

Here we enter a bit of a rabbit hole for a good cause. That cause has multiple aims: 1) to improve your confidence that coffee is indeed low in oxalate, 2) raise your awareness that academic journals publish junk science and generate misinformation and, 3) provide an object lesson in the value of taking some time to read the fine print.

Popular Summary Lists Mostly Think the Oxalate Content of Coffee is Low

Lists of high and low oxalate foods from medical centers mostly agree that coffee is low in oxalate (see Table 1. Online Patient-Education Lists from 4 North American Medical Centers). Agreement does not necessarily make them right, nor has it vanquished the ubiquitous confusion about coffee’s oxalate content. Urologists, the public, and even the researchers can’t get or give a straight or consistent answer about oxalate levels. Some medical researchers and clinicians believe that coffee is high in oxalate. I have friends in the medical field who believe it. And they use it as an excuse to resist learning about oxalate or controlling how much they consume. Any threat to the love of their life (coffee) will not be brooked.

Still, there are two solid scientific reasons to believe that coffee is very low in oxalate. The first is that all reputable testing to date has demonstrated that coffee is low in oxalate. The second is the real-world experience of low-oxalate dieters who have maintained a daily coffee habit with health benefits and without signs of oxalate-related symptoms. Other beverages, including hot chocolate, black tea, and green tea, have consistently been found to be high in oxalate and tend to trigger oxalate-related effects (the effects are variable—e.g. night-time irritable bladder).

I have a suspicion that the rumor about coffee being high oxalate originated in confusing reports on the oxalate content of instant coffee powder, which led to misinterpretation of the results. Instant coffee is indeed very high if you eat a whole cup of the undiluted powder. However, no one does that! Instead only about 2g is dissolved in a cup of hot water. The University of Pittsburgh’s patient education lists (Table 1) use a seemingly escalated number for instant coffee (greater than 10 mg per cup). Perhaps their source mistook the powdered coffee’s oxalate content for what is present in a reconstituted cup.

Table 1.

Online Lists of Oxalate Content of Foods

From North American Medical Centers (Patient Education Materials)Instead of relying on shaky lists, let’s go to the primary sources to consider results reported by credible researchers regarding the oxalate content of coffee.

Published Analyses of the Oxalate Content of Coffee

Oddly, published tests of the oxalate in coffee are relatively few. Perhaps this is because virtually all historically reported tests have found both brewed and instant coffee to be “very low” in oxalate for typical serving sizes (see Table 2. Publications Reporting Oxalate Content in Coffee: Plain and Two Flavored Coffees). There are two articles listed in Table 3 that claim coffee is high in oxalate. I will examine these articles in detail below.

Given that the question appears to be resolved, perhaps that is why testing coffee seems to be uninteresting to researchers. Nobody gets published in a quality journal if they’re reporting one more example of the same old uninteresting result. Lack of interest may perpetuate confusion regarding oxalate content in coffee, as it does for so many other foods.

Table 2 lists 11 published results (from 8 sources) reporting the oxalate content of coffee. These tests analyzed various types of coffee (instant and brewed), as well as two Starbucks flavored coffees. The researchers used a variety of analytical methods.

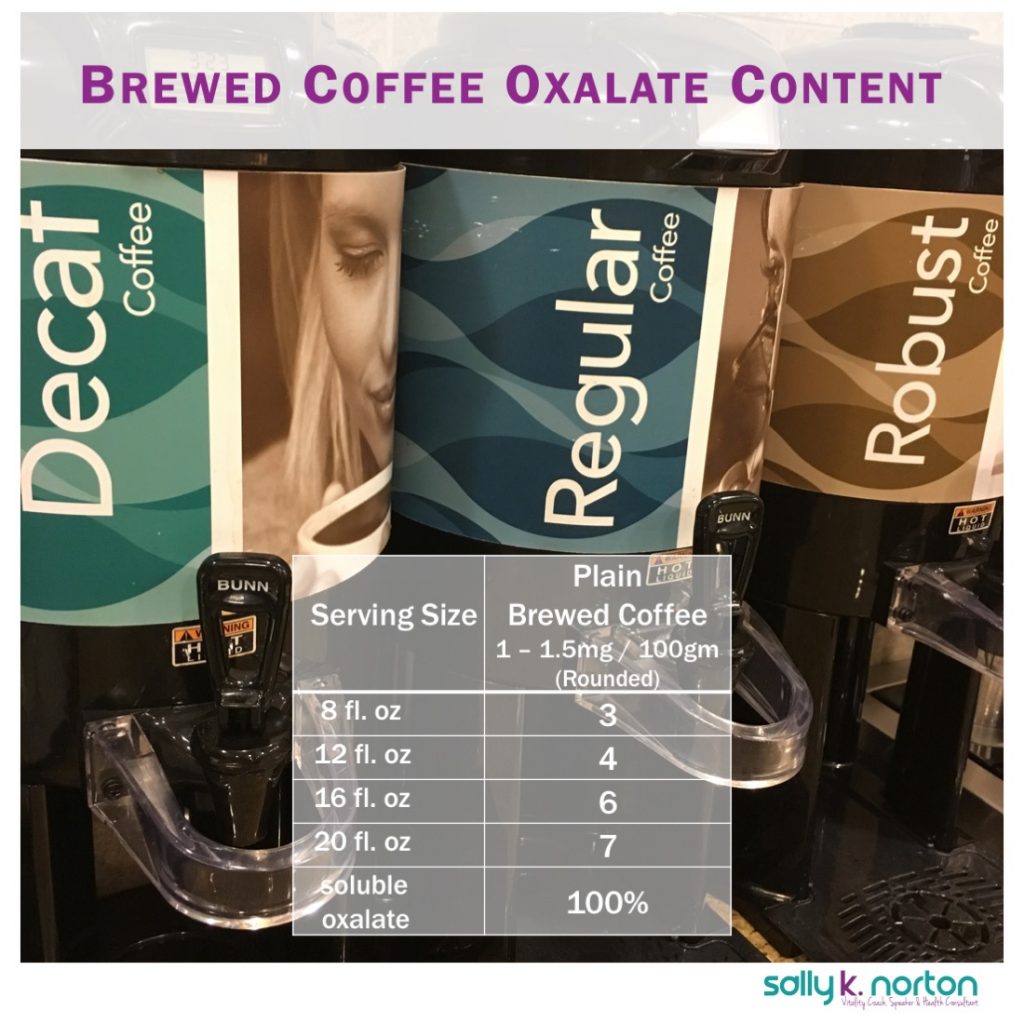

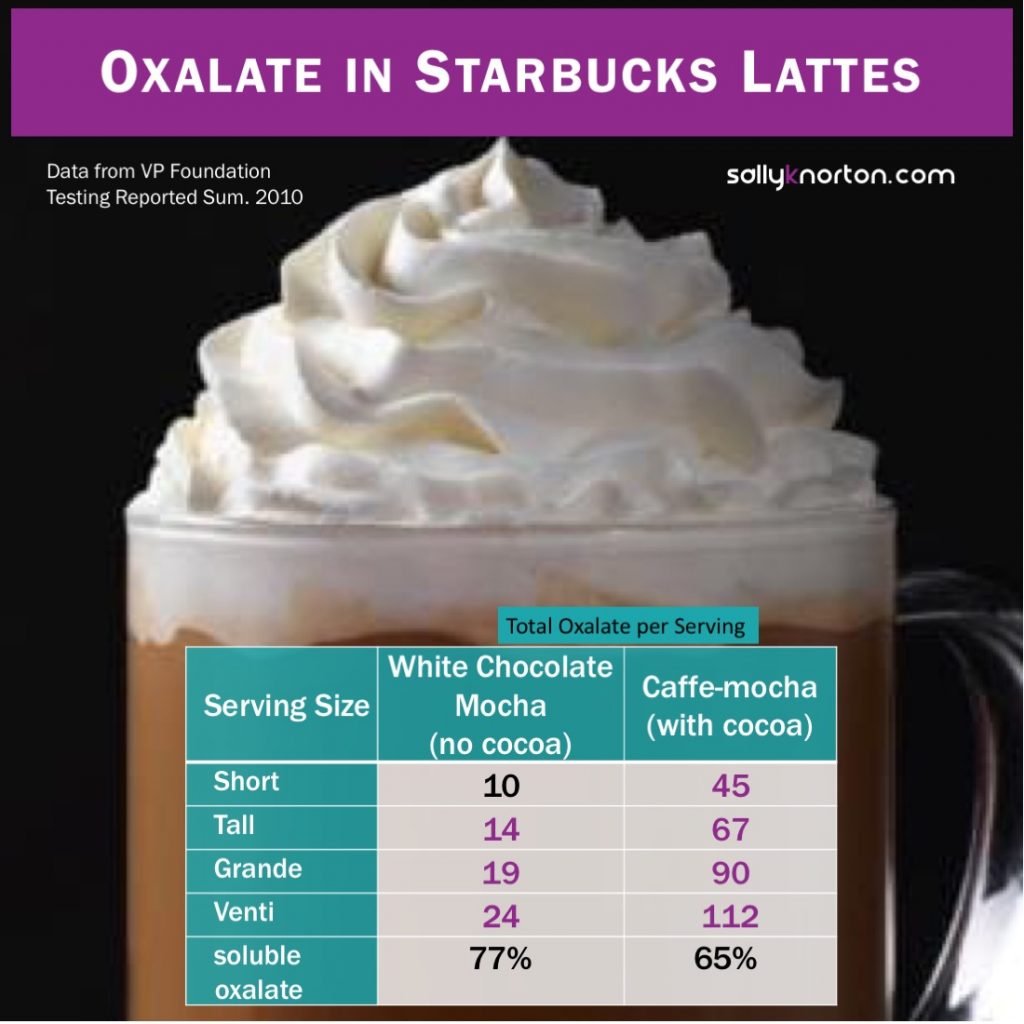

The rightmost column in Table 2 reports milligrams of oxalate in an eight-ounce serving (237 ml). Instant and unflavored brewed coffee have somewhere between 0.7 and 2.4 milligrams of oxalate per cup. Flavored coffees may have higher oxalate content coming from ingredients other than the coffee. In particular, notice that a Starbucks mocha latte has 47 mg of oxalate per cup, which is high – but at least 80% of that oxalate is coming from the (chocolate) mocha.

Keep in mind that today’s mugs, like our waistlines, have gotten rather large. Eight ounces is roughly what you get in a “short” Starbucks cup. A typical small takeout coffee is usually twelve ounces (Starbucks “tall”), a medium size is 16 ounces (Starbucks “grande”), and a large is 20 ounces (Starbucks “venti”). Scale the oxalate results accordingly. Portion size always makes a difference, but fortunately coffee is low enough that the oxalate hit even from a large-sized unflavored coffee won’t be especially dramatic.

Table 2

Publications Reporting Oxalate Content in Coffee:

Plain and Two Flavored Coffees| Year | Reference | Analytical Method | Variety Tested | Data as reported | Mg Per 8 ounce (237 ml) serving |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Zarembski and Hodgkinson ((Zarembski PM, Hodgkinson A. The oxalic acid content of English diets. British Journal of Nutrition. 1962;16(01):627. doi:10.1079/BJN19620061)) | Colorimetric determination of ether-extracted, acid-processed sample | Nescafe Instant powder | 57mg/100g powder | 0.7 (Estimated as if prepared using 0.5 g powder per 100 ml) |

| 1962 | Zarembski and Hodgkinson ((Zarembski PM, Hodgkinson A. The oxalic acid content of English diets. British Journal of Nutrition. 1962;16(01):627. doi:10.1079/BJN19620061)) | Colorimetric determination of ether-extracted, acid-processed sample | Ground Arabica with 5% chicory; 2mg powder/100g water, infused for 5-minutes | 1mg/100g liquid | 2.4 |

| 1980 | Kasidas and Rose ((Kasidas GP, Rose GA. Oxalate content of some common foods: determination by an enzymatic method. J Hum Nutr. 1980;34(4):255-266)) | Enzyme (oxalate decarboxylase) assay modified for food analysis | Nescafe Instant | 3.2mg/ liter prepared 0.5g powder per 100ml water | 0.8 |

| 1992/1993 | Elmadfa et al (cited in ((Hönow R, Hesse A. Comparison of extraction methods for the determination of soluble and total oxalate in foods by HPLC-enzyme-reactor. Food Chemistry. 2002;78(4):511-521. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00212-1))) | Unknown | Unknown | 1mg/100g brewed | 2.4 |

| 1995 | McKay et al ((McKay DW, Seviour JP, Comerford A, Vasdev S, Massey LK. Herbal Tea: An Alternative to Regular Tea for those who Form Calcium Oxalate Stones. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1995;95(3):360-361. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00093-3)) | Enzyme assay | Maxwell House Drip | 1.6 mg per 250ml (8.4 ounces) brewed. | 1.5 |

| 1997 | Clinic Ciba-Geigy (cited in ((Hönow R, Hesse A. Comparison of extraction methods for the determination of soluble and total oxalate in foods by HPLC-enzyme-reactor. Food Chemistry. 2002;78(4):511-521. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00212-1))) | Unknown | Unknown | 1mg/100g brewed | 2.4 |

| 2002 | Hönow and Hesse ((Hönow R, Hesse A. Comparison of extraction methods for the determination of soluble and total oxalate in foods by HPLC-enzyme-reactor. Food Chemistry. 2002;78(4):511-521. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00212-1)) | High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with Enzyme-Reactor | Brewed 30g coffee per Liter | 0.5 – 0.7 mg/100g brewed | 1.4 |

| 2004 | Galli and Barbas ((Galli V, Barbas C. Capillary electrophoresis for the analysis of short-chain organic acids in coffee. Journal of Chromatography A. 2004;1032(1):299-304. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2003.09.028)) | Capillary electrophoresis | Roasted Colombian | 25.6mg/100g ground coffee (not brewed) | 1.8 est. for standard brewed equiv.: 30g per liter water |

| 2004 | Galli and Barbas ((Galli V, Barbas C. Capillary electrophoresis for the analysis of short-chain organic acids in coffee. Journal of Chromatography A. 2004;1032(1):299-304. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2003.09.028)) | Capillary electrophoresis | Lyophilised Colombian coffee | 17mg/100g ground coffee (not brewed) | 1.2 est. for standard brewed equiv.: 30g per liter water |

| 2010 | Liebman / VP Foundation ((The Low Oxalate Diet Addendum Summer 2010 - Numerical Values Table. The VP Foundation Newsletter. 2010;(34) )) | Capillary electrophoresis or enzymatic assay (not specified) | Starbucks | 4.3 mg/100g | 10 (“short”) |

| 2010 | Liebman / VP Foundation ((The Low Oxalate Diet Addendum Summer 2010 - Numerical Values Table. The VP Foundation Newsletter. 2010;(34) )) | Capillary electrophoresis or enzymatic assay (not specified) | Starbucks | 20 mg/100g | 47 (“short”) |

Low-Hanging Fruit: Rotten or Not!

Let’s take a close look at the two studies that report that coffee is very high in oxalate.

If you’re expecting the latest publication to offer a definitive answer, you will be misled when you find the 2012 article from Elzbieta Rusinek ((Rusinek E. Evaluation of soluble oxalates content in infusions of different kinds of tea and coffee available on the Polish market. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2012;63(1):25-30)) which reports very high numbers for the oxalate content in coffee (Table 3: Studies Claiming Coffee is High). Rusinek published in a Polish journal that appears in Pubmed (the online research database of the National Institutes of Health). The easiest article to find when you search for “coffee” and “oxalate” is Rusinek’s. When you look over Table 2, you’ll see that the studies by McKay and by Hönow and Hesse don’t use the word “coffee” in the title of their articles, nor do they have coffee as a key word, making those articles difficult to find.

In addition to being the easiest to find, the full text of the Rusinek article is also freely available to anyone with an internet connection because the journal is an “open access” publication where all articles are free to download. In stark contrast to being free and accessible, the majority of bio-medical studies are issued by publishers expecting payment from readers. if you’re not affiliated with a university (which may pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for subscriptions), you might have to pay $35 or $40 dollars to read or download a single paper, such as the Hönow and Hesse article. Such articles are described as being behind a “paywall”.

How do we explain these very different results?

The trouble with the 2012 Rusinek study is that it seems to be junk. However, that is not obvious to non-chemists. I’ve reported Rusinek’s results, and the results from another Polish study that she was emulating methodologically, in Table 3. Those results state that brewed coffee has 71 to 114 mg of oxalate per cup, and that instant has 110 to 361 mg of oxalate per cup.

All the other recent studies (since 1990) have found coffee to have 1.5 – 2.5mg of oxalate per cup. These two Polish studies report that coffee is nearly forty times higher than all previous studies! Even though Rusinek herself was scratching her head over the vast disparity of her results, she made no effort to determine why her results differed and she published them anyway. With mushy language, she offers readers a vague excuse for her results and their “apparent divergence”; here’s the full passage:

“It is difficult to compare the studies presenting the results of the soluble oxalates analyses in the instant and ground coffees with our results because of their apparent divergence. The result of determinations of oxalates content in teas and coffees is influenced by the various analytical methods of different sensitivity used, as well as processes related to acquisition followed by burning, grinding and mixing procedures, extraction conditions and the initial mass of the sample.”

Rusinek, E (2012) ((Rusinek E. Evaluation of soluble oxalates content in infusions of different kinds of tea and coffee available on the Polish market. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2012;63(1):25-30)), p. 29

Table 3

Studies Claiming Coffee is High In Oxalate

Hint: Do not believe them!| Year | Reference | Analytical Method | Varieties Tested | Data as Reported | Mg Per 8 ounce (237 ml) serving |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Sperkowska and Bazylak ((Sperkowska B, Bazylak G. Evaluation of oxalate content in brews of black teas and coffees available in Poland. Nauka Przyroda Technologie. 2010;4(3):#42. doi:10.17306/J.NPT.2010.3.42)) | Potassium Permanganate Titration | Various ground available in Poland | 47.94 mg/ 100g brewed; 796 mg/100g dry | 114 (brewed) |

| 2010 | Sperkowska and Bazylak ((Sperkowska B, Bazylak G. Evaluation of oxalate content in brews of black teas and coffees available in Poland. Nauka Przyroda Technologie. 2010;4(3):#42. doi:10.17306/J.NPT.2010.3.42)) | Potassium Permanganate Titration | Various instant coffees available in Poland | 152.19 mg/100g prepared; 2536 mg/100g dry | 361 (reconstituted instant) |

| 2012 | Rusinek ((Rusinek E. Evaluation of soluble oxalates content in infusions of different kinds of tea and coffee available on the Polish market. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2012;63(1):25-30)) | Potassium Permanganate Titration | Various ground and instant available in Poland | 18-40 mg /100g for brewed and 37-56 mg/100g for reconstituted instant. | 71 (brewed) 110 (reconstituted instant) |

Exposed: Bad Methods, Laziness and Sloppiness

To understand why Rusinek’s article is bad science, the next sections of this post consider her poor choice of method, her failure to consider other methods, and errors of fact in her paper. If you don’t have patience for learning about the science, you can skip to the last section on how to make sense of oxalate data.

Permanganate Titration is an Unreliable Method for Measuring Oxalate

Truth be told, it’s pretty likely that the discrepancy begins with the fact that Rusinek (and Sperkowska and Bazyluk, the other paper in Table 3) used an outdated analytic method called permanganate titration. This method uses a titrant, permanganate, to generate a litmus-like test of oxalate content. The persistence of a light pink color indicates that the reaction of the permanganate with the oxalate is complete. Here is Rusinek’s description: “Titration in hot temperature was conducted with 0.02 N solution of potassium permanganate until pink color appeared and remained for about 1 minute.” p.27

There are several inherent problems with permanganate titration. For one, it is very easy to over-estimate the amount of the material (oxalate in this case) that is being sought with this method. Lab instructions for performing this test explain that the overestimate happens because the permanganate ion is able to “autocatalyze” its own destruction which requires additional (excess) permanganate titrant to reach the endpoint. The oxalate content is determined by measuring how much of the titrant was consumed, so if the permanganate consumes itself the result is going to overstate the amount of oxalate.

But there are other problems with the permanganate titration method. In their 1980 study on oxalate in foods, GP Kasidas and GA Rose ((Kasidas GP, Rose GA. Oxalate content of some common foods: determination by an enzymatic method. J Hum Nutr. 1980;34(4):255-266)) point out that “…substances such as citrate could be extracted with oxalate and might have interfered with the subsequent precipitation and titration with permanganate.”2 But you can go back 20 years earlier and see that the perils of using the permanganate method were already well-known by the early 1960s. At that time UK-based leaders in the oxalate field, PM Zarembski and A Hodgkinson ((Zarembski PM, Hodgkinson A. The oxalic acid content of English diets. British Journal of Nutrition. 1962;16(01):627. doi:10.1079/BJN19620061)), concluded that alternative colorimetric procedures are less subject to processing-related issues and therefore preferred over the permanganate titration method.

Rusinek does not explain the reasons for choosing an inferior method of analysis that had been out of favor for about 50 years prior to her publication. We can safely conclude that Rusinek’s analytical methods contributed to her wildly skewed results. Given her poor choice of method and lack of comparison to more widely accepted methods, Rusinek’s results can confidently be classified as spurious.

Good Scientists Study their Methods, not just their Samples

It is interesting to compare Ruth Hönow and Albrecht Hesse’s 2002 article ((Hönow R, Hesse A. Comparison of extraction methods for the determination of soluble and total oxalate in foods by HPLC-enzyme-reactor. Food Chemistry. 2002;78(4):511-521. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(02)00212-1)) to Rusinek’s to get a sense of what happens with better science.

In the Department of Urology at the University of Bonn (Germany), Hönow and Hesse sought to validate a new, simpler method for testing oxalate content in food. They also explicitly wanted to determine if or when artifacts of the new testing process could skew their results. And when they tested cherries, they found that for some reason their approach led to higher estimates of oxalate content than previously reported. Instead of brandishing their new findings as “truth”, they did a detailed examination of what might have led their method to “go wrong”, including testing with an alternate method. The result is honest science, and a paper that not only reports believable data obtained using a credible method, but also carefully explains the advantages, pitfalls and limitations of the method.

Errors in Citing Previous Studies

Apart from the poor choice of analytic technique and lack of critical examination of the method and the results, there is one more reason to distrust Rusinek’s report. Her results for coffee deviated massively from every previous study. But in reporting the previous studies, she made misstatements that downplay just how big the deviation is.

First, she claimed falsely that Hönow and Hesse found an oxalate concentration of “10.6 mg/100 cm3 of infusion” (p. 29). In fact, they reported 0.5 to 0.7 mg/100g (see Table 2 above). (For purposes of comparison, 100 cm3 is the same as 100 ml, which for brewed coffee weighs almost exactly 100g, so the reported oxalate content is all on the same basis.)

Rusinek invented a number (10.6mg/100 cm3) that is twenty times larger than the real number (0.5 to 0.7 mg/100g). In doing so, Rusinek implied that her results are two to four times higher than Hönow and Hesse. However it’s much worse than that. If she were honest about the numbers, Rusinek would have to admit her results are 50 times higher: 71 mg per cup versus 1.4 mg per cup.

Our sloppy researcher makes another important citation mistake as well: “[C]onducted in the Sixties Zarembski and Hodgkinson’s studies on oxalic acid in the English diets the oxalates were at the level of 57.00 mg in the infusion of instant coffee (emphasis mine) ‘Nescafe’ from the Arabica beans which was prepared from 2 g sample soaked for 5 minutes with 100 cm3 water at 40°C.” But as shown in Table 1, the article reported 57mg for the instant coffee powder and not the infusion. Moreover, Zarembski and Hodgkinson did not analyze the prepared instant coffee, only the powder. The statement regarding their preparation method is also a “miscommunication”: the sample preparation method Rusinek describes is the one that Zarembski and Hodgkinson used for brewed coffee, not instant.

In her defense, Rusinek’s mistake is easy to make. Zarembski and Hodgkinson reported brewed coffee results on the basis of milligrams per liter of brewed coffee, yet they reported instant coffee on the basis of milligrams per 100g of dry powder. And I suspect the same mistake is probably happening in patient education materials like those in Table 1 when they decide that instant coffee is spectacularly high in oxalate: they are misinterpreting data presented as oxalate in powder or dry material as if it were the value for the prepared drink. If you’re making a cup of instant coffee from two grams of powder, and the powder has 57mg per 100g, you’re only getting 1.14mg of oxalate in that cup!

I’m not convinced that Rusinek’s sloppiness is entirely innocent. The effect of both these errors is to understate the magnitude of the discrepancy between her results and respected prior research by almost two orders of magnitude.

But Wait! Isn’t There Another Study Saying Coffee is High?

One more reference offered by Rusinek deserves comment (and inclusion next to her results in the Table 3 “Hall of Shame”). In support of her findings, Rusinek cites a 2010 article by Sperkowska and Bazylak published in another Polish journal ((Sperkowska B, Bazylak G. Evaluation of oxalate content in brews of black teas and coffees available in Poland. Nauka Przyroda Technologie. 2010;4(3):#42. doi:10.17306/J.NPT.2010.3.42)) . The study featured in that article appears methodologically identical to Rusinek’s: obtaining coffee and tea samples from local stores, brewing them up, and analyzing them with a harsh preparation process followed by permanganate titration for the measurement step.

Because the Sperkowska and Bazylak article is only available in Polish, I won’t take it on in detail. In the abstract (available in English), their tests found the amount of oxalate in instant coffee powder to be 25.36mg/g of dry mass, or 2.536 grams per 100 grams. In other words, they claim that 2.5% of the instant powder (by mass) is pure oxalate. If instant coffee really were that high, surely someone else using other methods would have noticed! And the vendors would probably make more money selling it as a cleaning product to remove stains from your coffee cup than as a food.

Why were these authors confused? Did they make mistakes? Did they lie? Did they have bad editors? Or did none of them really care what they were publishing? Regardless of how it happened, the bottom line is: low quality papers get accepted and published by seemingly respectable journals.

Other False Claims that Coffee is High in Oxalate

Another article available on Pubmed states bluntly in its title that coffee is a significant source of dietary oxalate. The reference is Gasińska and Gajewska (2007) ((A Gasińska, D Gajewska, Tea and coffee as the main sources of oxalate in diets of patients with kidney oxalate stones. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2007;58(1):61-7)) entitled “Tea and coffee as the main sources of oxalate in diets of patients with kidney oxalate stones.” (I presume it’s an odd coincidence that this study was published several years earlier in the same Polish journal as Rusinek’s later study. We’ll leave it to someone else to diagnose the curious and apparently unique compulsion for Polish researchers to publish claims that coffee is high in oxalate!)

Gasińska and Gajewska did not conduct any oxalate testing of foods eaten by kidney stone sufferers. Instead, the 2007 study surveyed kidney stone patients (using an unspecified food-frequency questionnaire and 3-day food record) about their diets, and used other published oxalate content numbers to estimate how much oxalate the patients had been eating and from what sources. They offered no real detail about how they performed this magic trick. The Food-Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) method is rife with pitfalls. For one, FFQs are not designed to distinguish between high and low oxalate foods. For example, spinach and arugula (opposite ends of the spectrum of oxalate content) are considered the same food type; and how much did you eat last year anyway?! Let’s not go any deeper into that annoying topic!

Here’s the stinker: Gasińska and Gajewska stated that their number for coffee oxalate content came from the 1995 McKay et al study ((McKay DW, Seviour JP, Comerford A, Vasdev S, Massey LK. Herbal Tea: An Alternative to Regular Tea for those who Form Calcium Oxalate Stones. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1995;95(3):360-361. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00093-3)). Specifically, they write: “The intake of oxalate was estimated on the basis of [a] table with oxalate concentration in tea and coffee by McKay et al” (Gasińska and Gajewska, p.62). But the McKay study (see Table 2 above) showed that coffee was very low! And the problem is not just that Gasińska and Gajewska misread the data table from McKay. They apparently also didn’t read the article text, where McKay et al state bluntly “Coffee prepared by the drip method was also found to have a low oxalate content–similar to that of herbal teas” (McKay et al, p.361).

So clearly the editors and reviewers of the Gasińska and Gajewska article did a terrible job of fact-checking. (For crying out loud, people, how can you put “coffee” in the title and not check the source?) At best, their article might support the assertion that tea is a major source of dietary oxalate. But that’s not news, and their coffee claim amounts to garbage.

These problematic articles that put the word “coffee” in the title are free. They appear in a seemingly legitimate journal, and in the index on Pubmed, so they must be true, right? Almost no one takes the time to correct the record or have these studies retracted.

And that, dear internet, is how bad science takes flight and lives on and on and on.

How do you make sense of oxalate data?

A lot of the information on the internet about oxalate content for any food (not just coffee) is problematic. The USDA table, for example, is filled with errors and only offers a tiny set of foods. Mistakes get introduced into the record as a result of a combination of outdated or inaccurate testing, bad math (and misinterpretation of what is actually being reported), and poor availability of the science. Even in good research, the numbers are often not reported in units that dietitians and consumers can use directly.

Because of the variability in testing procedures and in the foods themselves, there is always some uncertainty. It would be great if there were programs in operation that would repeatedly:

- Sample lots of common foods;

- Be specific about the botanical variety being tested and its state of freshness and ripeness;

- Describe in detail the culinary preparation methods;

- Test the foods multiple times for oxalate content using a variety of analytical methods;

- Describe the methods in detail, and

- Present the results in a format that can be used to calculate dietary intake of oxalate.

For now, we’ll just have to keep making do with what has been reported by responsible researchers: plain coffee, even instant, has under 3mg of oxalate per cup. Let’s hope that the growing interest in the benefits of low-oxalate eating will inspire better standards and more publication of results that are reliable. We should also call attention to bad data on websites (and get the bad data off the USDA list of oxalate content).

Thanks for making it all the way through this technical article. I hope it is a valuable example of how bad science is abundant and problematic.

Disclaimer

I want to point out explicitly that I am not myself a coffee-drinker, and I wouldn’t personally recommend coffee to anyone. I’m not “defending” it because I want to drink coffee, but rather because I have a strong commitment to convey complete, honest, and useful information (and call “BS” when I see it).