Oxalate Answers, A Quick Outline

1. Oxalic acid: What is it?

- A naturally occurring tiny molecule that is a toxic, corrosive acid

- When it has minerals attached to it, it is called Oxalate (OX). (chemically a salt)

(E.g. sodium oxalate, potassium oxalate, magnesium oxalate, calcium oxalate)

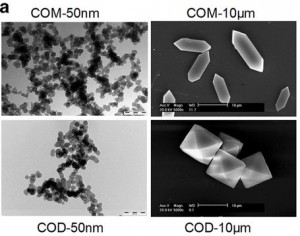

Oxalate likes to form crystals. Most kidney stones contain calcium oxalate.

2. Where does oxalic acid come from?

- Plants make it, possibly for mineral management, seed germination, or self-defense

- You eat it, in many foods. It comes in many forms, both dissolved and as crystals, in a variety of shapes and sizes

- Some foods have a lot of it, some have very little

- Examples of High OX Foods:

beans, grains, bran, sesame and other seeds, peanuts, almonds, and other nuts, swiss chard, spinach, beets, potatoes, chocolate, rhubarb, figs, kiwi, blackberries, black pepper, cumin, turmeric. - Examples of Low OX Foods:

meats, dairy, eggs, fats and oils, and other non-plant foods

arugula, avocado, Bok Choy, cabbage, cauliflower, cilantro, cucumber, garlic, kohlrabi, lettuce, mustard greens, mushrooms, green peas, watercress

- Your body makes it. Oxalate is a metabolic waste product in mammals with no known function

- Higher amounts are made when:

- Deficient in B6, or

- High doses of vitamin C are taken or injected

- Higher amounts are made when:

- Some fungi make it, possibly for mineral management, especially in soil

- Can be made by Aspergillus fungi living in the body

- However, there is no scientific evidence that I have found that Candida produces oxalate in the body or that it contributes in any significant way to our body’s oxalate load

3. How can oxalate harm you?

- The body has no way to disarm oxalate and must excrete it. When cells are required to handle oxalate they are moving it or “managing” it, not metabolizing it. This is dangerous work for a cell.

- It steals minerals from your diet and your body and makes them useless (it is an “anti-nutrient”)

- Soluble forms of oxalate (sodium oxalate and potassium oxalate) can be picked up by other minerals like magnesium, calcium, iron, zinc, copper, etc. This locks up the mineral. Oxalate may also bind with toxic metals such as lead, mercury, aluminum, or cadmium.

- Mineral deficiency causes growth, reproductive, and other problems

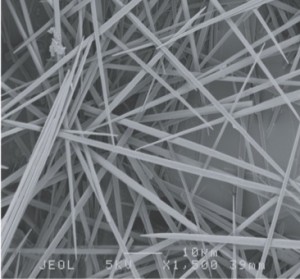

- It is corrosive to the lining of the digestive system, may cause leaky gut or other GI diseases. Some OX crystals have a needle shape known to perforate mucus membrane cells.

- Challenges the kidneys and can overwhelm their capacity to remove oxalates from the blood

- Forms nanocrystals and microcrystals that can collect in the body and irritate tissues

- crystals can collect in any body tissue, even the plaque in your arteries

- kidney stones usually contain oxalate crystals

- Soluble forms of oxalate are absorbed from food and trigger inflammation, causing:

- Membrane and mitochondria damage, and cell death (fatigue and energy issues)

- Nerve cell damage, pain, and functional problems associated with the brain and nerves

- Dysfunction of cells, organs, glands

- Depletion of the antioxidant glutathione in cells. Low levels of glutathione can generate superoxide radicals, increasing toxic stress causing early cell death. Glutathione is especially important in the liver for the detoxification of chemicals. It is also important in preserving brain health.

- Cell communication problems (autoimmunity, hormonal issues, neurological issues). For example: Ox can confuse and stress the immune system, creating auto-immune symptoms.

- Destroys connective tissue’s key building block (hyaluronic acid)

- makes it much harder to fully recover from injury, even surgery

- can weaken or destabilize joints, bones, skin (skin may be thin or easily damaged)

- can make you injury prone

- May deplete the B-vitamins, B6 and biotin

- Uses up vitamin B6, possibly initiating a vicious cycle. B6 deficiency increases internal production of oxalate, increases oxalate load, further depleting B6, and so on.

- Can alter biotin metabolism, depleting biotin

- Can lead to a wide range of problems, throughout the body

- Kidney damage

- Damage to intestines, may contribute to the development of celiac disease and “leaky gut”

- Breathing problems, mucus production, and congestion

- Brain problems – sleep, mood, behavior, cognition, organizational ability, autism

- Urinary issues and genital pain

- Gum and tooth problems

- Bone and connective tissue instability

- Contributes to aging, and can make you feel old prematurely

- These problems don’t always cause obvious symptoms. Onset may include a generalized malaise, poor concentration, some sort of “-itis” (gastroenteritis, tendonitis), joint stiffness, swelling, muscle pain or weakness.

- Oxalate damage is not a sensitivity or allergy. It is a toxicity problem.

- Reversal of oxalate toxicity is an avoidance and excretion issue. It is not a matter of boosting liver function as is typically addressed in “detox” regimens.

4. How and why are the crystals formed?

- Science is studying these questions, because we don’t know enough yet. It is hard to study oxalate handling, distribution, and oxalate crystal deposition in the body.

- Blood delivers oxalates to tissues; higher concentrations of oxalates and a number of other factors may encourage crystallization and deposits in the body.

- Injured tissue is prone to oxalate deposits. Cell fragments may become hosts to OX crystal formation and growth.

- Too little citrate allows for crystallization of oxalate.

- Sometimes oxalate molecules attached to membrane fats don’t grow into crystals, even these non-crystalline oxalate deposits disturb cell biochemistry

5. Why does it affect some people and not others?

- We don’t know how many people are affected by dietary oxalate. Excessive exposure to oxalate is generally unrecognized and is hard to identify and quantify.

- Even patients with known high-oxalate problems are often described as “asymptomatic” in the medical literature. This means it can be hard to know if oxalates are causing damage to your health. Eventually a problem will develop, such as a kidney stone, but you typically don’t know that it is happening until it gets really bad.

- When symptoms are present, they don’t neatly correlate with recent intake of oxalate, but instead may flair up as the body releases oxalate, when less oxalate has been consumed. Measures of blood oxalate and urine oxalate do not necessarily correlate with symptoms, for many reasons.

- The problems associated with oxalate toxicity are presumed to have other causes and factors generating these symptoms. Oxalate rarely gets the blame, even in part, for the problems they are capable of causing.

- Modern lifestyles may be increasing the number of people affected by dietary oxalate, by increasing exposure and lowering our tolerance.

- It is easier than ever to eat high oxalate diet. High-oxalate foods are now more accessible year-round and very popular. Ironically, the health-conscious may have a greater affinity for some high-oxalate foods such spinach and almonds which are promoted as healthy.

- The oxalates we munch on may be more readily absorbed and less efficiently excreted due to our reliance on medications, including over-the-counter pain and cold medications and popular prescription drugs. These drugs can harm the gut flora and function, and reduce the kidneys’ ability to remove them from the body.

- Adequate oxalate excretion can also be impaired by other toxic exposures, such as indoor air pollution, which can erode kidney function.

- Gastro-intestinal resection surgeries dramatically increase susceptibility to food oxalates.

- The potential for harm from a high oxalate diet can be magnified by other factors besides the health and function of the gastro-intestinal (GI) tract and kidneys.

- The mix of foods within your meals affects how much oxalate is absorbed and how much your body has had to handle over your lifetime. For example, meals rich in calcium and fiber can lower the amount of oxalate absorbed from foods, while diets low in fiber and calcium may increase the amount of oxalate you absorb.

- Gender and other genetic factors affect the way the body handles oxalate. Women are less prone to kidney stones, but more prone to pain syndromes.

- Fetal exposure to oxalate and other toxins may set the stage for oxalate trouble, perhaps including autism and other brain function issues, such as learning and behavior problems.

- Older people have less efficient function of their kidneys and digestive processes, and more years of oxalate exposure and accumulation. They may thus be especially vulnerable to the toxic effects of oxalate.

- High oxalate intake when inflammation is occurring allows for more tissue deposits and more damage.

- Deficiencies of vitamins and minerals may aggravate oxalate’s toxic effects. Heavy drinkers, the obese, and those who have undergone gastric bypass surgery are at especially high risk for micro-nutrient deficiencies.

- There are undoubtedly many other factors we have yet to discover and document.

6. How can I know if oxalates are an issue for me?

- There is no sure way to determine the extent that oxalate is causing health issues. Most health care providers are not even aware of this possibility.

- Accepted medical tests for oxalate accumulation in the body involve taking tissue samples from kidneys, bones, or skin. Biopsies are invasive tests that are reserved for the rare situation when there is strong clinical evidence for advanced kidney failure with a genetic component.

- Urine tests measuring oxalate are not reliable because of natural variations in urine content. Some people with advanced kidney deposits of oxalate have very little oxalate in their urine. The more extensive the oxalate deposits are in the urinary tract, the more likely that excessive oxalates become trapped there instead of being released into the urine. Thus, low levels of oxalate in the urine are not necessarily reassuring. The body needs to be capable of continuously excreting oxalate. High levels of oxalate in urine may indicate that the kidneys are indeed able to excrete oxalate despite a heavy work load, either from a recent meal, from high levels of internal production, or from the release of body stores of oxalate. High urine oxalate maybe a sign that the body is reversing the accumulation of oxalates in the body, once the source of oxalate has been adequately limited.

- The low-oxalate diet itself can offer some strong indicators, when the diet is implemented correctly and consistently. This requires accurate data on the oxalate content of foods. You also need to know how to recognize common reactions.

- Often, a person with oxalate issues will experience some temporary worsening of several symptoms after being on a truly low oxalate diet for a while. This could be a sign that cells are moving stored oxalate out and being damaged in the process. Sticking with the diet is an important part of waiting out the healing process.

- There is no single pattern of symptoms that identifies oxalate toxicity, everyone has their own unique set of reactions to over-exposure to oxalates. But there are patterns of symptoms that are often associated with oxalate toxicity. If you have ever had kidney stones, or if you have three or more of the following problems, you may benefit from lowering your oxalate consumption:

- Kidney infections

- GI problems, or have had GI surgery, especially colon re-sectioning and gastric by-pass

- You have pain that comes and goes without obvious cause, or that affects different body parts on different days.

- You have pain or weakness in the arms, hands, legs, or feet

- You have back stiffness or pain

- Your urine is frequently cloudy or hazy looking

- You don’t sleep well or are tired a lot

- You have other brain function problems: brain fog, cognitive losses, mental fatigue

- You have incomplete recovery from injury or surgery

- You tend to have disappointing responses to both conventional and alternative therapies

- You eat one or more high-oxalate foods daily